IV. But…Why Pick on Businesses?

We’ve now seen some quite compelling reasons to enact Corporate Responsibility Rankings. But what about the reasons not to enact it? It’s hard to say for sure, but it’s likely that the number one objection to CRR is that it will be bad for businesses.

Pretty much any new business regulation gets backlash for being “anti-business.” However, to some this law may sound even worse. CRR is going to make companies give up data on everything they do behind closed doors AND make them spend boatloads of money on solar panels and pay raises?! That’s an outrageous violation of privacy! And it’s going to bankrupt our businesses, to boot! What’s more, why are we picking on businesses to start with? We’re the ones who buy their cheap stuff. We’re the ones who enable them to pollute and pay dirt poor wages. If we want to change these problems, we should be the ones changing, not the hard-working businesses that drive our economy.

These are important criticisms. If they’re right, then CR Rankings could do our economy plenty of harm. However, as we will attempt to prove below, CRR will be quite good for the economy, businesses are exactly whom we should be targeting, and their claims to privacy make no sense. Within the overall “bad-for-business” complaint, let’s go through each of these more specific complaints one at a time.

1. Businesses don’t deserve this headache

To begin with, we have the basic argument that businesses don’t deserve all of this unneeded regulation. We already tie the hands of our job creators too much. This just adds more bureaucracy, red tape, and headaches.

However, businesses absolutely deserve to be targeted by a ranking system like CRR. Simply put, they make most of the mess in this world. Businesses—if we combine the commercial, industrial, and agricultural sectors—account for about 65% of all greenhouse gas emissions in the US.1-7 (while producing all the rest). They make most all of the non-biodegradable plastic that now floats in our oceans, and they run all of the sweatshops. They account for over 88% of global water consumption,8 and here in the US they host over 85% of the wage-paying jobs.9,10 If we want to seriously address Global Commons Motivation (GCM) problems—problems like global warming, antibiotic resistance, toxic chemical consumption, non-biodegradable plastics, unsafe working conditions, water shortages, and income inequality—we simply have to target businesses because they’re the ones making the vast majority of the mess that creates these problems.

That’s not being anti-business. It’s just being reasonable. If you don’t like how dirty the kitchen floor gets every day and most of that dirt comes in the form of muddy paw prints, then the solution should be pretty obvious. Find a way to stop the dog from tracking in more mud. Ignore the dog’s contribution and you’d be a fool. The same goes for cleaning up GCM problems. Any real solution has to focus on getting our businesses to stop making such a mess. Focus anywhere else and you won’t actually fix the problems.

2. Mandatory = bad for business

Next up, there are no doubt those who will criticize CR Rankings simply for being mandatory. Anything mandatory handed down from the government to our businesses is bound to be trouble. You’re impinging on the freedom of businesses! How will tying the hands of our job producers make anything better?!

We’ve already touched on the merits of the mandatory system over its voluntary counterparts in Our Current Approach Is Doomed To Fail, but this is a bit of a separate issue. Even if mandatory systems are much more effective than voluntary ones, maybe they’re still too cumbersome for businesses. Maybe they’ll stop global warming…but also grind our economy to a halt in the process. That, of course, would be a pretty bad tradeoff.

Note that to cooperate with CRR, though, no business has to do much of anything. No business has to pay its workers any differently, use electricity any differently, etc. It only has to report the required data and print the labels. There is, in other words, a big difference between mandatory action and mandatory transparency.

A mandatory action is something specific a business must do, as decided by the government. Building codes dictate the width of hallways and how many outlets there must be on a wall. The EPA forbids manufacturers from using certain chemicals. Overtime pay laws tell businesses how much they must pay their employees past forty hours of work in a week. While mandatory actions do a lot of good, it’s understandable why business owners can chafe at them. Mandatory actions don’t allow much freedom in how they’re accomplished, and put together they can make for quite a headache of extra work.

The Surgeon General's warning on cigarette packs mandates transparency, not action.

Debora Cartagena/CDC

With mandatory transparency, on the other hand, businesses can still mostly do whatever they want. They just then have to show the public what they’re doing. Tobacco companies can still make and sell cigarettes, for example, but they have to put the surgeon general’s warning on each pack. Similarly, no food company has to bake some exact amount of fat, sodium, and carbs into its crackers. That company just has to report honestly how much of those nutrients are in its crackers on the Nutrition Facts label. Exact fat and sodium requirements would be mandatory action. Nutrition Facts are mandatory transparency. One way means totally changing your business. The other means dealing with a slight annoyance. The difference is huge. CR Rankings would similarly only mandate transparency, and would thus be much less of a pain in the behind.

Nutrition Facts are, in fact, perhaps the best existing parallel to CRR. What Nutrition Facts did for food ingredients, CRR would do for the behind-the-scenes impact of companies on the world. So if we’re at all worried about the burden of implementing CRR on companies, let’s ask ourselves honestly how burdensome Nutrition Facts have been to tally up and print on boxes. Have Nutrition Facts crippled the American food industry? Have our newspapers of the last forty years been packed with the tragic bankruptcies of US cereal, beef, and juice companies? No. The notion is absurd. So too, CR Rankings would likely cause a few growing pains when first instituted, but should give no real drag to the economy like, at worst, mandatory actions sometimes can.

3. CRR would be too expensive for businesses

Third, we have the complaint that CRR would cost too much money. Most businesses aren’t raking in huge profits. The reason they don’t give bigger raises to their employees is that they can’t afford to do so. They can’t afford to give away millions to charity. They can’t afford to spend their employee hours tinkering away in the basement on a new, biodegradable soda bottle. Simply put, they can’t afford to go fixing the world’s problems.

This is a damning critique of CR Rankings and one that we must absolutely address if we are to justify enacting this ranking system. It’s quite a tempting thought, the too expensive argument. If true, CRR stands to both cripple the economy and fail to make any positive change. However, this argument just doesn’t hold water, for several reasons.

First, CRR would encourage companies to spend money to be more responsible, sure, but such companies would only do this spending if they choose to do so. It’s still totally up to them. And those times that they do choose to spend that money will be because they think it will make them more money back (a.k.a. a profit).

Blake Patterson/Wikimedia Commons

It’s essentially the same as when companies invest money on any other project. Consider Apple and the iPhone. Did it cost the company plenty of money to create the first iPhone? Absolutely. The price tag was reportedly, in fact, something in the massive range of $150 million.11 But Apple didn’t spend all of this money because the government or anyone else forced them to do so. They did it because they hoped there would be a high demand for their new product. And sure enough there was. Apple now makes tens of billions of dollars every few months off of the iPhone,12 easily surpassing the down payment needed to build the smart phone in the first place.

CR Rankings might not put any business in the same out-of-this-world profit ballpark as the iPhone did for Apple (what else can, really?), but the same idea would apply. Any company considering giving that big raise, making that million-dollar donation to Unicef, or daring to design that new biodegradable plastic bottle would only make such investments if it thought such investments would boost its CR Rankings, win the company new customers, and thus outweigh the initial costs of those investments with even bigger profits. In other words, businesses would only make such investments if they thought those investments would overall be profitable. So moaning on behalf of the poor victims of CR Rankings is as nonsensical as lamenting the suffering of Apple as it created the iPhone. CRR should only cost businesses money that they will expect to make back.

Externalities

Second, it doesn’t make much sense to complain of the cost of CRR for businesses because any added expense is one that business arguably should have been paying for in the first place. Remember that mess from before? The carbon dioxide emitted, the water consumed, the low wages paid that all lead to GCM problems? Someone has to pay for the consequences of that mess, so why shouldn’t it be the companies that make it?

Economists call these externalities. Externalities are the hidden costs of an action that the doer of that action doesn’t have to pay for. Let’s say, for example, that you take a camping trip in the Smoky Mountains for some good, cheap fun. You have to pay for gas, food, and maybe some extra camping supplies, but that’s it. Sounds great! But beneath that light bill are some hidden costs. Roads had to be paved to get you there, trails had to be built for you to walk on, and both have to be regularly maintained. On top of that your car emits carbon dioxide and other pollutants that slightly contribute to rising sea levels and increased rates of respiratory illnesses. Aside from a tiny sliver of your taxes, you won’t directly pay for any of that. These are your camping trip’s externalities.

Businesses, meanwhile, rack up a ton of externalities. Endless job movement tears apart communities. Tax avoidance creates large government deficits. Toxic chemicals create many millions of health problems. These are expensive problems, yet the businesses that create them rarely end up paying the bill.

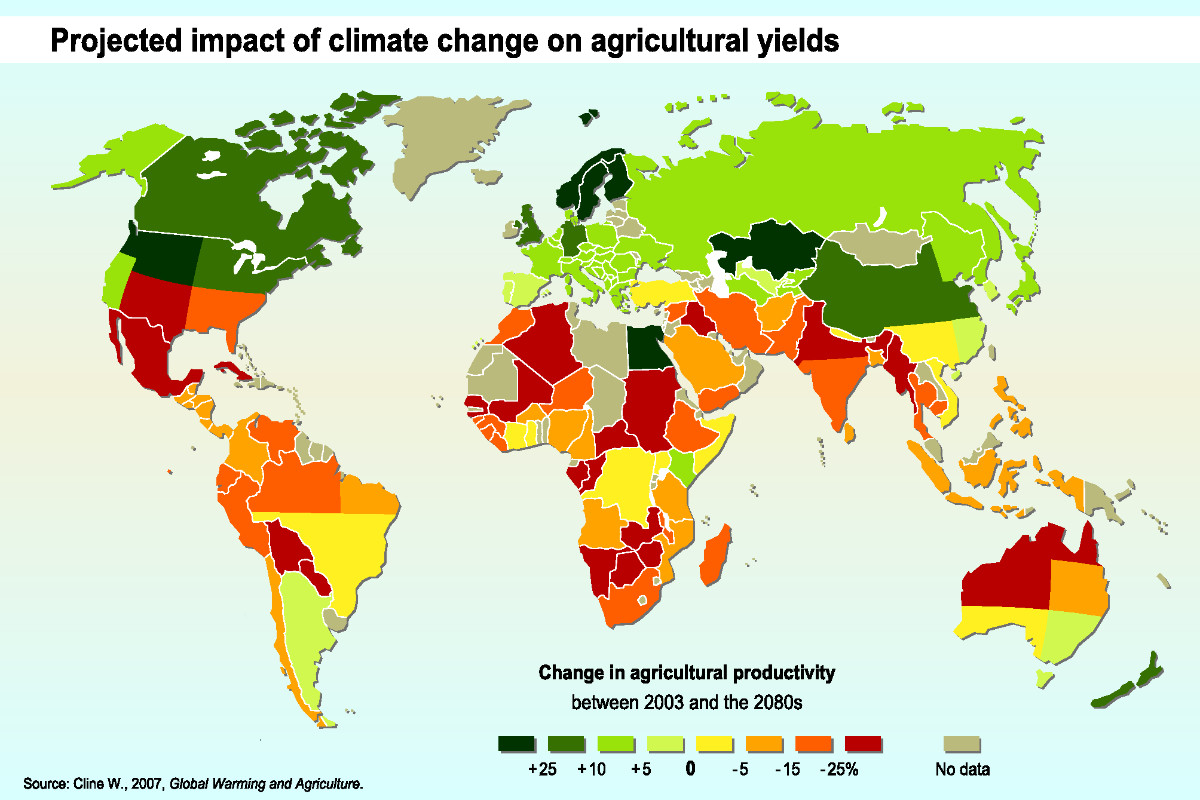

For an even bigger externality of business-as-usual, take global warming. The Counsel of Economic Advisors to the White House recently put out its best estimate of $36 as the current social cost of each ton of carbon dioxide emitted into the atmosphere.13 That means each ton of CO2 causes about $36 in cumulative damages to the world, through lost crop production due to drought, building and infrastructure damage due to rising sea levels and more violent storms, etc. Thirty-six dollars might not sound like much until we step back and look at the bigger picture. In the US, about 6.87 billion tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (CDE) were produced in 2014 alone.14 That equates to a social cost of $247.3 billion. If that number doesn’t sound staggering enough, the $36 government estimate has actually been critiqued by others in the field as being too optimistically low. Scientists from Stanford published a study in January 2015 estimating the true social cost of CDE to be more like $220 per ton,15 which would put the total social cost of US greenhouse gases that year at $1.51 trillion. Whichever way you go on these estimates, remember that businesses produce almost two-thirds of the greenhouse gases in this country, and are therefore responsible for almost two-thirds of the bill. That’s something in the range of $160 to $979 billion of damage US businesses do each year via climate change,16 essentially none of which they actually pay for.

Crop yields are projected to change quite a bit thanks to climate change, mostly for the worse.

European Environment Agency

And then there is the massive externality stemming from income inequality. When businesses don’t pay those at the bottom of society well enough to get by, the government has traditionally had to step in to help. The five biggest programs here in the US to provide health care, food, and small amounts of financial assistance to the poor gave out $681.1 billion in 2014.17 A good amount of that is arguably the cost of some inevitable unemployment, of course (so perhaps the blame shouldn’t be on businesses there), but a study by researchers at UC Berkley found that, of the money the government spent on those same five programs from 2009 to 2011, 56% went to working families.18 In other words, that’s another $350 billion dollars of mess directly created because businesses don’t pay their lower-end employees well enough to pay for their basic needs.

It’s hard to pinpoint an exact sum of these externalities, but we can at least see that here in the US they tally into the many hundreds of billions of dollars each year. And since businesses are the ones racking up the bill, they absolutely deserve to be the ones paying it. If CR Rankings push companies to pay to clean up this mess, then all the better.

4. CRR’s data collection is a pain for businesses and a violation of their privacy

Next up, we have the notion that the data that CRR requires businesses to give to the government is too invasive. This program wants to be Big Brother looking over the shoulder of our businesses 24/7. It’s creepy, and it’s wrong. Would we let the government know what products you the citizen buy and what your electric bill is? No, that would be ridiculous! Forcing businesses to tell the government this same information is just as ridiculous. Keeping track of all of this data would also be a tedious pain for companies. It will distract them from doing the real work they need to be doing.

First, let’s address the complaint that logging and reporting all of this data would be a big pain. Perhaps here it would be good to review what kind of data the government would be collecting. We invite you to look further into the specifics in Data Needed, but this data mostly boils down to:

1.) What things businesses are buying

2.) What they’re selling

3.) How much they’re paying their employees

and

4.) What resources they’re collecting from the earth

These are all pretty basic pieces of information. Any responsible company should already be keeping detailed track of this data. (Good luck trying to stay in business for long if you aren’t.) The exact specifics of how to log the information, in what format, and in what computer program will no doubt change a bit thanks to CRR, but the overall task shouldn’t change much. Businesses will have to keep inventory of what they’re doing. Nothing too new there.

As far as reporting the data, it would be done on a quarterly basis, much like taxes. For the vast majority of companies it would be done automatically online. (Anyone can still mail the information in if they really want to do it that way.) The government would design its own free programs and apps for submitting this information, but any outside company would be free to design its own reporting programs too (think TurboTax but for CR Rankings). Plus, other apps, computer programs, and websites could in time be designed to coordinate with your CRR program of choice. Buy something on Amazon with your corporate account and, boom, it’s automatically logged in your CRR reporting program. The process would no doubt be a bit bumpy at first, but before long businesses would hardly have to do anything but let such information be collected and sent automatically each quarter.

So all in all, it really shouldn’t be very tough to log and report this data. If it ever does end up being unnecessarily hard, though, the CRR reporting process could absolutely change. One of the number one goals of the program would be to make this data process as painless for businesses as possible, with regular reviews of feedback from the business community to make sure that it’s going as smoothly as possible.

Now, some still may object to gathering this data on ideological grounds, though. The government shouldn’t be able to collect this info, period. Businesses have a right to privacy.

Sure, it makes sense to allow a good amount of privacy for businesses. Making strategic decisions and designing new products, for example, should absolutely be kept private. Accordingly, CR Rankings would do nothing to broadcast such private decisions. Your five-year plan for expansion? Tell no one, that’s a-ok! The revolutionary new gaming console you’re releasing next year? Keep us all in suspense, no worries!

But what about the data CR Rankings would collect, like what a company pays its workers and what it’s buying and selling? Do companies deserve privacy there, too? Privacy seems like a pretty fair demand on the surface, but look deeper and it pretty quickly falls apart.

First off, hopefully on a gut level it makes sense that people deserve much more privacy than companies. Companies aren’t people. Companies don’t want to hide their actions because they’re of an intimate, vulnerable nature like we do. What Viacom pays its executives isn’t the same as what you whisper to your kids when they’re going to bed. How many gallons of gas Wal-Mart burns in a year isn’t the same as how many TV shows you watch or how many times you have sex in a year. Businesses don’t deserve the same right to privacy as people do because they don’t have that same sacred inner life.

But there’s also a more logical justification for this difference. Those private actions of yours—the whispering, the TV-watching, the sex—can be kept private because they don’t do significant harm to anyone else. Note that the times we do draw the line and stop citizens from doing something are when they are significantly harming others. Even if you do it at home behind closed doors, you still can’t physically abuse your wife, kill your husband, or starve your children. These are times when society says, no, you’ve stepped over a line. Here we will use our police, courts, and jails to keep you from doing this harm to others. Note the underlying reason here. When your actions start to do significant harm to someone else, you can no longer claim a right to privacy because your actions then cease to be private. They are now public actions.

The same goes for businesses. When a company cuts down a forest, pays thousands of employees, or emits millions of tons of carbon dioxide, its actions are significantly affecting others in potentially very harmful ways. Thus, businesses have no right to privacy with such actions. These actions are instead inherently public. Thus, the government is absolutely justified to collect data on such actions for CR Rankings. Any claim to a right to privacy here is like a wife abuser claiming that he should have a right to privately abuse his wife, too. Because harm is being done, the right to privacy ceases to exist.

So, overall, businesses don’t really have room to complain about the data that CRR would collect. Every business should already be collecting such information anyway, so keeping track of it shouldn’t be very tough. With the internet and specially designed computer programs, reporting that info to the government shouldn’t be hard either. And because all of that information revolves around potentially harmful actions, businesses have no right to withhold it.

5. We the citizens (or perhaps the government) should be the main focus for change, not businesses

Finally, the last main reason one might say CRR shouldn’t be targeting businesses is that there are better, easier ways to eliminate GCM problems. Namely, we should be focusing our efforts directly through citizens and the government, not businesses. Fixing our biggest problems needs to start with us. If we all make changes at home like switching to compact fluorescent light bulbs, volunteering more, and simply buying less stuff, we can start to turn around problems like global warming. For whatever we can’t do at home, we should be looking to traditional government fixes like raising the minimum wage, boosting welfare programs, and raising taxes on the rich. Businesses shouldn’t really be a part of this.

This is another fairly inevitable critique of CR Rankings. It should especially be expected from a lot of liberals who think that, well, this rankings system sounds pretty cool and all, but really these home and government fixes are all we need. We just need to push a bit harder, change a few more minds, and get a few more favorable election results.

It’s another tempting thought, but one that ultimately doesn’t add up too well. To understand why, let’s zoom out further than we have so far and look at the big picture. Hidden beneath our differing views on how to solve GCM problems is often a sharp difference in whom to target. There are essentially three main groups we can target: citizens, government, and businesses. Each time we focus primarily on one, we put the other two into pretty consistent supporting roles. And what we’ll find is that citizen and government-focused approaches are rather weak both because of both their main focuses and the supporting roles they create.

The Citizen-Focused Approach

Seattle Municipal Archives/Flickr

Citizens (primary role): Make the small changes that we can at home. Recycle, use less stuff, buy more energy-efficient machines, donate to charities, and volunteer occasionally.

Government (supporting role): Teach and encourage consumers to be better to the environment, pass laws that facilitate their action (like ENERGY STAR labels and tax breaks that encourage donations).

Businesses (supporting role): Mimic the government by encouraging citizens to “go green” and then occasionally start programs that get customers to donate and volunteer more.

Grade: D

Meet Doug. Doug manages a seafood restaurant. For the most part Doug is a normal guy. He wears polo shirts and tells corny jokes. He swears in traffic. He sometimes forgets to pay the rent on time, often lets dishes pile up in the sink, and can’t help thinking plenty of spiteful thoughts throughout his day. That being said, though, Doug tries to do a decent amount of good for the world. He buys fair trade socks and organic soap. He recycles. Plenty of the groceries Doug buys are of the normal, General Mills-and-Pepsi variety, sure, but he also loads up about half his cart in the natural foods section. He turns the lights off when he leaves a room. When possible he bikes instead of driving. Every once in a while he volunteers with Habitat for Humanity, and you probably don’t have to give that persuasive of a pitch to get him to donate to a charity. If he’s got the money, Doug is happy to donate. Doug is always happy to do what small things he can to do good.

Sound familiar? You probably know a Do-Gooder Doug, if not many such people. (The fact that you’re reading this argument here makes it highly likely you’re a Do-Gooder Doug yourself.) Some may find Doug a bit annoying for being such a goody-two-shoes, but all told we should commend him for doing everything he can to make the world a better place. Put together, his actions make a real, very positive difference.

However, there’s an important, often overlooked question that we need to ask here. How much of a combined difference do the Do-Gooder Dougs of the world actually make? After all, we often hear that homespun citizen action isn’t just a good thing to do—it’s the thing to do. Many tout such small actions like recycling and volunteering more as the answer to problems like overflowing landfills, homelessness, and global warming. But if we are to actually fix such GCM problems then we need to first take a cold, sobering look at the tools we’re trying to use to get there. And although we enthusiastically commend the Dougs of the world, this citizen-focused approach just doesn’t do nearly enough.

The Citizen-Focused Approach Comes up Way Short

Think about how the citizen-focused approach has generally fared thus far. We’ve been recycling at home for over a half-century in the United States, and yet it still doesn’t stop us from producing well over a hundred million tons of un-recycled trash each year.19 We donate plenty to charities, but that hasn’t managed to stop the rise of inequality (much less to then start to shrink it). Volunteering is so common that for many it has replaced going to churches, temples, and mosques as the preferred weekly act of penance. But realistically it has yet to come anywhere close to ending poverty, hunger, or homelessness. Such citizen acts are all still helpful things to do, but we’ve already been doing them for decades and they haven’t stopped the rise of our GCM problems. So why do we think tomorrow is suddenly going to be magically different? The good that these actions do is simply much too little for this citizen-focused approach to be our primary weapon to take GCM problems down.

Note, for example, how this approach fares with global warming. We’ve all heard the tips of what we can do at home to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Recycle more, use compact fluorescent light bulbs, turn down the thermostat in the winter and up in the summer. These are probably the three most common recommendations. So what would happen if all of us actually did them? What if we doubled all recycling, replaced every incandescent bulb in America with a CFL, and all followed Energy.gov’s recommendations for thermostat jiggering to a T? Achieving all three of those would essentially be a home conservation grand slam, an amazing, too-good-to-be-true breakthrough…and yet they would still only reduce our GHG emissions by approximately 4.85% (as calculated with arguably fairly generous estimates).20-28 That isn’t all that much. To put that hypothetical number in perspective, let’s look at another number that is very much real: 0.8%. That’s our current yearly rate of population growth in the US.29,30 And with those extra people all consuming more energy come more greenhouse gases emitted every year. In other words, those gains made by that recycling, CFL, and thermostat grand slam? They should be wiped out with less than six years of natural population growth.31 Good as these actions sound, they just aren’t nearly enough to take down GCM problems like global warming.

Of course, proponents of the citizen-focused approach might say, well of course you only have a small reduction in GHG there because those three changes are only the beginning! What about better home insulation, biking to work, turning off the lights when you aren’t in the room, buying more efficient machines, keeping your car tires better inflated, and so on?

These are all great things to do, too, but no matter what they’re still inherently limited. Remember that businesses create about 65% of the greenhouse gases here, meaning we the citizens only produce the other third or so. So even if by some ridiculous miracle we were to completely eliminate all greenhouse gases from our homes and cars (quite the miracle indeed), the majority of our country’s GHG production would remain, and global temperatures would continue to dramatically rise. In other words, no matter whether we all become the most do-gooding Do-Gooder Dougs we can be at home, global warming is still set to spiral out of control.

Going Off The Grid

But wait. The citizen-focused approach isn’t done quite yet. There are a hardy few out there who would say the do-gooding we just detailed would only fail because we still need to go even further. If businesses are the ones creating 65% of a problem like greenhouse gases, then stop contributing to that 65%. Simply stop buying their products.

This brings us to Do-Gooder Doug’s wife, Self-Sufficient Susan. Susan works as a junior architect downtown. Through work connections she’s accumulated a lot of salvaged wood, wood that she has then repurposed into two chairs, several beautiful sculptures, and all of her kitchen shelving. She also mends clothes instead of throwing them out and has sewn two new dresses. Years ago she started a small garden in the backyard. After expanding each year, that garden pretty much now is the backyard, growing dozens of different fruits, vegetables, and herbs. Whatever Susan can’t grow she tries to buy at the local farmer’s market. And since Doug moved in, they’ve been trying to save up enough money to put solar panels on the garage.

As with Doug’s efforts to better the world, Susan’s efforts no doubt do a lot of good, too. But again, the question we need to ask is whether this kind of self-sufficiency is the best route to taking down GCM problems. Is it a viable solution to push everyone to become Self-Sufficient Susans? Many a starry-eyed idealist would say yes. And the upside is that doing so we could actually each bring our carbon footprint down close to zero. (Which is huge!) But to do so we’d realistically have to go far beyond Susan—to get off the power grid, completely stop driving cars, stop buying anything except home-made goods from neighbors, and start making all of our own clothes from home-grown hemp and animal hides.

The issue here isn’t whether this solution would be effective. It arguably would. The problem is something that you already know. It’s something that you can already feel deep in the pit of your stomach as you’re reading this right now. It’s that there’s no way in hell this is ever going to happen.

There’s no need to disrespect this ultra self-sufficient, off-the-grid lifestyle because if that works for you, hey, that’s fantastic. But to expect a massive cultural shift wherein we’re all going to do so is completely bananas. The overwhelming trend of human history, for millions of years and on every inhabited continent, has been towards people buying and using more stuff to be safer, better fed, and more comfortable. Human nature is human nature, regardless of how much that starry-eyed idealist wants it to be something else. Thus, every time the idealist preaches this ascetic lifestyle, everyone else rolls their eyes and continues on with their lives.

If it’s any indication of how unlikely such a massive cultural shift is, note that people have been so preaching that we recycle more, volunteer more, and go live the simple life in the woods for decades, and yet the amount that we actually do such things hasn’t really changed. Recycling rates have remained flat, the percent somewhere in the low thirties, since the 1990s.32,33 The percentage of Americans that volunteer has stayed similarly stable. If anything, it has slightly dropped since the early 2000s.34 So if we can’t preach people into recycling or volunteering more, why do we think we can preach them into much bigger changes?

Therein lies the key weakness of the citizen-focused approach. As it’s used now, it’s nowhere near enough to actually fix GCM problems. And to actually be enough to fix GCM problems, this approach would need to be taken to laughable extremes, ones that are simply impossible given human nature, no matter how much we preach that we need to push more toward such extremes. And thus the citizen-focused approach strikes out.

Weak Supporting Roles

If that wasn’t enough, the citizen-focused approach has still more issues. First, for certain problems there are essentially no practical things you can do at home to help. There’s no high-tech green toilet you can buy to reduce income inequality, for example.

And then there’s the issue of innovation. In order to combat GCM problems, we will inevitably need a lot of new discoveries to be made: more efficient electronics, less toxic manufacturing processes, and new renewable energy technologies, just to name a few. However, the citizen-focused approach doesn’t at all lend well to such discoveries. Maybe you’re the kind of brilliant genius who, using your own money and spare time, can design a new, twice-as-efficient method for burning biofuels out in your garage. But my bet is you’re not that kind of person (no offense). Pretty much no one is, if only because of the whole spare time and money thing. The citizen-focused approach thus has big holes. It doesn’t do enough overall, certain problems are left completely untouched, and it fosters a lack of innovation.

Meanwhile, that’s just the primary role for citizens. When we look to citizens as the main agents for big change, we also put the government and our businesses into regular supporting roles. And those supporting roles don’t fare too well, either. The government turns into a goading, shaming nanny. It makes TV commercials with a lot of boring stats on how good recycling is and then wags its finger at citizens when they don’t take heed and recycle more. Businesses, meanwhile, get to slink back into the background, sadly nod in agreement, and then do almost nothing themselves to help. They may facilitate certain initiatives to help citizens do more—like a grocery store collecting back plastic bags from shoppers to then recycle them—but this mostly just helps them look good and gives them a free pass to then otherwise be as irresponsible as they’d like. Oh, look over here at what we’re so generously doing to collect and recycle plastic bags…so that you don’t think about how we’re making all of these wasteful, polluting plastic bags in the first place.

The citizen-focused approach is extremely limited. The changes we citizens can realistically make right now just don’t make that big of an impact. What’s more, they put the government and businesses into weak supporting roles where they don’t do much to help, either.

The Government-Focused Approach

Anna Waters/Flickr

Government (primary): Pass laws that force the changes that we need to see happen (the minimum wage, Clean Water Act, higher taxes, USDA Organic, etc).

Citizens (supporting): Vote for legislators that will pass the laws we prefer, then do whatever else is needed to sway those legislators to vote for certain laws (contact them, attend protests, sign petitions, donate to campaigns, work with unions).

Businesses (supporting): Abide by the laws that the government passes (but then otherwise keep doing whatever’s cheapest).

Grade: C

Just down the street from Doug and Susan live a young couple named Polly and Paul. Polly and Paul drink a lot of coffee, speak confidently, walk fast, and wear a lot of smart black outfits. They recycle like Doug and Susan and admire the backyard garden, but their focus is more on politics. Polly runs a political advocacy group that pushes labor reform. Paul works as a business consultant but also volunteers with political campaigns on the side. On weekends they stuff mailers for Polly’s non-profit. Cable news and the New York Times are regular members of the family, although they never seem too welcome. (The more they’re around, the more Polly and Paul grimace, groan, and shout.)

Political Paul and Polly ardently believe in a government-focused approach to fixing the world’s problems. A government-focused approach is one in which the government is the main driver of change. Pretty much all classic labor, environment, and tax laws fall into this category. Each seeks to drive change through government action. The minimum wage forces companies to raise pay below a specific level, thus reducing poverty. The Clean Air Act sets specific limits on pollutants that can be emitted to keep us healthy. The Kyoto Protocol sets government-formed targets for greenhouse gas reductions. In each case, our governments are the ones deciding what exactly will change and then enforcing it. (You don’t, of course, have to be super into politics to believe in the government-focused approach. Across the street Voting Vince and Val rarely think about big global problems, but they trust that voting for the right officials every year or two will mostly set things straight.)

Now, the Political Pauls of the world (and to a lesser degree the Voting Vals) tend to think that, if the government-focused approach hasn’t fixed certain problems yet, it still will. Any delay occurs because a.) the other political side is morally bankrupt and is taking us in the wrong direction and b.) we just need to push harder to pass the traditional legislation we’ve long been fighting for. This means to fix our problems you should get out and vote. Voice your opinions. Donate to campaigns you believe in. Help register new voters. Work directly with a campaign. The more we can do to push our side over the finish line, the sooner we can get the laws passed that we’ve known for decades will fix our problems.

Let’s for now ignore the dubious assumption that the other side is always wrong in politics. What about the we-just-need-to-push-harder part? Can the government-focused approach actually knock out global warming if we just do a better job pushing for more laws? Unfortunately no. Up against GCM problems, our traditional legislative approaches fall pretty flat. They always have and they always will.

Bad Motivation

If you recall from Our Current Approach Is Doomed to Fail, we talked in great depth about how minimum bar laws and voluntary transparency programs—the government’s two main approaches to fixing most anything—do a pretty good job with baseline problems but thoroughly fail to fix GCM problems. To fix any motivation problem, you must give those who are behaving badly the strong, consistent motivation to completely weed out that bad behavior. The MB laws and VT programs that we create just don’t really do so, though. Because the minimum wage doesn’t give businesses that needed motivation to pay most of its employees better, the law doesn’t do much to keep income inequality from rising. Because the Clean Air Act doesn’t motivate companies to keep reducing its toxic pollutants below a permitted maximum, the law won’t stop Americans from breathing in enough pollution to acquire major health problems. And because the Kyoto Protocol hardly motivates anyone to whittle away at their carbon footprints at all, the agreement has done almost nothing to stop global warming.

But there’s more. The impotence of the laws we pass isn’t the only huge downfall of the government-focused approach. With this approach also come strong headwinds that push legislators away from passing and strengthening these laws in the first place.

If you watch politics much you’ll know how the game works. What are most any politician’s top three priorities? Jobs, jobs, and more jobs. In order to keep the voters happy, every politician’s home district needs plentiful jobs. In order to have plentiful jobs, you need to keep the companies that provide those local jobs happy. And in order to keep those local companies happy, you need to keep the cost of business down. That means politicians face a constant pressure to keep the minimum wage low, corporate tax rates low, environmental restrictions lax, and electricity options cheap. Do otherwise, by, say, building a series of solar power plants and passing a law that requires more overtime pay, and you raise that cost of business a little bit. That risks scaring away local companies and making it harder to attract new ones. And with fewer companies come fewer jobs, more pissed off voters, and thus, for the backwards ending to this sad little game, a pink slip for the do-gooder politician. Hence, because politicians are scared to pass them, stricter regulatory laws and cleaner power plants always face a steep uphill battle.

So far, the government-focused approach isn’t looking so hot. The laws it passes are rather weak, and that’s if they can ever get passed in the first place. Market forces consistently push politicians in the complete opposite direction.

Powerless Voters and Selfish Businesses

How about the supporting roles for citizens and businesses? Do they fare any better this time? Sadly, no. The business’s role, when being regulated by whatever new laws, is to take the punishment that the government deals out then continue to be as irresponsible as it can get away with. If the government says you can’t emit more than x amount of mercury, then change just barely enough to pass the regulation. If it says you have to pay a certain percent in taxes, then pay just barely enough. Better yet, look for tax loopholes in the law so you can legally pay even less.

Again, we covered this quite in depth in Our Current Approach Is Doomed to Fail, but essentially note that businesses are geared to do battle with, water down, and avoid the government’s laws, all of which drastically undermines the goals of better responsibility. In other words, businesses are motivated to do the exact opposite of what the government’s laws set out to do. That doesn’t make for a good supporting partner in change.

Meanwhile, the citizen’s main role in the government-focused approach is mostly to vote. But we each only get one political vote a year. Plus, if we’re talking about the elections that actually matter, it’s more like one vote every four years. Add on top of that that most of us live in uncompetitive states and voting districts, and our votes matter all the less because it’s incredibly unlikely that each citizen’s one individual vote will sway any final outcome. That gives us citizens very little power to create positive change when the focus is on government action.

Overall, the government-focused approach is not a very good one if our goal is to address GCM problems. The laws it passes are inherently flawed, and the forces in the system push against passing those laws in the first place. The supporting roles for business and government are even weaker. This system encourages businesses to go against everything the government passes and leaves the citizen powerless to do much of anything but watch with frustrated dismay. It’s no wonder Polly and Paul react with so many groans and shouts to the government news they see playing out on TV.

The Business-Focused Approach (Current)

Walmart Corporate/Flickr

Businesses (primary): Sometimes do small things to help workers, environment, and communities (but only whatever is affordable at the time and which, ideally, will also get the company good press).

Citizens (supporting): Occasionally try to buy from more responsible companies to support the ones who are doing good things, but most always get confused in this quest, give up, and do nothing.

Government (supporting): Try to shame companies into making more responsible choices with angry speeches and the occasional congressional inquiry but ultimately do very little.

Grade: F

If the citizen and government-focused approaches to change are bad, then the business-focused approach is far worse.

The current business-focused approach to GCM problems is essentially, hey, let’s get out of the way of our businesses, hope for the best, and see if they use their brilliance to fix these problems. This is the approach conservatives seem to favor the most. Let the innovators innovate! That kind of thing.

However, the way things stand now, calling this an actual “approach” to solving GCM problems is laughable. Remember that the market currently pushes businesses to be as irresponsible as they can get away with—to pollute the air, underpay their workers, and avoid their taxes as much as possible. In other words, they’re motivated to do the exact opposite of fixing these problems. So why would this approach ever succeed in fixing GCM problems? It’s a bit like trying to keep hungry dogs from eating a stash of bacon…by putting those same hungry dogs in charge of guarding it. This is so stupid a plan that it almost isn’t worth mentioning. Obviously the dogs “guarding” the bacon would quickly turn to competing to see which one can gobble it all down the fastest. But the same goes for corporations. As long as their motivation is to be as irresponsible as possible, trusting them to police their own irresponsibility is just as nuts.

There are, of course, plenty of organizations working to help businesses be more responsible (the Dow Jones Sustainability Index, for example). And a lot of companies make a big show of joining these programs and trying to act more responsibly. These businesses check all of the right boxes. They line up new “green” priorities. They start some new after school arts program or canned food drive. And after spending small scraps of money on charitable causes, they spend similar amounts of money documenting these efforts for heartwarming commercials that convince you just how good these companies really are. But after the dust settles, the amount of bad they do for the world is clear and well documented, yet the amount of actual good they do is quite tiny in comparison.

For instance, the average household contribution to charity in the US is $2,97435 or about 5.7% of total income.36,37 Corporations, meanwhile, gave just 0.98% of their profits in 2015.38,39 And that isn’t just a much lower percentage than what we the citizens gave. That’s of their profits (i.e., the extra money left over after paying all of its employees, production costs, etc). The percent of total income would be much lower. If corporations were a person, they would rank somewhere around the abysmal Ebenezer Scrooge level in their support of charities.

Keep in mind that we don’t say this to demonize businesses, but instead to show how poorly the current business-focused approach to fixing GCM problems works. The current system pushes businesses to be as irresponsible (and do as little good) as they can get away with. Thus, as the system stands it’s lunacy to expect businesses to lead the charge in fixing problems of irresponsibility.

As for the supporting roles this time around? Unfortunately, citizens and the government are quite powerless here. The citizen is left to try to buy from more responsible companies, but how does anyone know which companies are the more responsible ones? For every label like USDA Organic that genuinely shows a product was more responsibly made, there are several others making vague claims to illegitimately mooch off of that responsible vibe. Products tell you they’re “green,” “natural,” or “sustainable” with no evidence to support these claims. And then the vast majority of products give no indication of how they’re made at all. So the citizen is left quite clueless and thus powerless to support any positive change. The government, meanwhile, here mostly devolves into the lead shamer, the preacher whom no one really listens to. It invites companies like Apple to a congressional hearing, as the Senate did in 2013, to chew them out for avoiding paying their taxes. Then it watches helplessly as companies like Apple continue right on not paying those taxes.

In the current business-focused approach, the primary group has no incentive to make any legitimate changes for the better. So it doesn’t. The two supporting groups (citizens and the government) have almost no power to make them do any better. Overall, the business-focused “approach” is really no approach to fixing GCM problems at all. It is the almost complete lack of an approach.

The Real Business-Focused Approach: CR Rankings

What happens, though, when we bring Corporate Responsibility Rankings onto the scene? This would still be a business-focused approach, one that looks to our businesses to drive change. This time, though, because higher CR Rankings would lead to more sales, those businesses would actually be given the needed motivation to drive such change. It’s like taking those dogs off of the bacon stash and having them guard their one-day-old puppies instead. Because the incentives would now do a 180o and line up in the right direction, those dogs would go from awfully suited to the task to perfectly suited to it. It’s the same for businesses after we enact CR Rankings. Their innovative talents would now be geared towards being more responsible, not less.

Here’s how our three groups would look this time:

Businesses (primary): Constantly innovate and make bit-by-bit improvements to better treat workers, environment, and communities.

Citizens (supporting): Use their immense purchasing power to push companies in productive directions with each purchase made every day.

Government (supporting): Act as referee by gathering data, calculating and distributing rankings, refining the system as needed, and resolving any disputes.

Grade: A

We’ve already well covered the power of CR Rankings to motivate businesses to do good. Suffice it to say, though, that this power would be immense. CRR would unleash a never-ending wave of innovations geared toward finally eliminating GCM problems like excessive income inequality and global warming.

Perhaps the key to why this business-focused approach would beat out the others is that it takes advantage of business’s two natural strengths: innovation and competition. Businesses have always experimented with new changes and then doggedly fought to adopt the best changes first. Now they would just use both of these strengths towards making the world a better place. Especially note here that these are both novel strengths that the citizen and government-focused approaches lack. When we rely on citizens to buy more energy-efficient refrigerators, those citizens have to rely on what’s available in stores. They don’t, that is, regularly take apart their fridges and tinker with more efficient designs themselves. We also don’t compete with each other to see whose house can turn down the thermostat the most in the winter, each going lower and lower till we’re down in the fifty-degree range. The government is similarly weak here. It has no one to compete with and mostly only innovates new military technology. Businesses would regularly do such fridge tinkering, though, and use natural competition to edge home heating systems to become more and more efficient every year. With this regular innovation and competition, the business-focused approach would over time blow the other approaches away in how much change it can accomplish.

But as significant as the business’s primary role in this approach is, the supporting roles of citizens and the government would be almost as significantly improved.

The Perfect Supporting Roles

First, let’s look at citizens in a world with CR Rankings. When the government is the focus, citizens play the rather powerless supporting role of voting once every few years in mostly noncompetitive elections. CR Rankings, on the other hand, would give you the power to vote every time you make a purchase. That’s several times you can easily vote for a better world every day. And as opposed to the citizen-focused approach, we could make huge gains in knocking out GCM problems while living the way we actually want to live—without, that is, having to go survive off of squirrel meat in a remote, electricity-free cabin. And remember all of those more efficient, environmentally-friendly products we’re supposed to buy in the citizen-focused approach? With CRR, businesses would be much more motivated to make such energy-efficient TVs, cars, and toilets (and phase out less-efficient ones). We the citizens could thus do a much better job of home conservation thanks to CRR than we ever can now. Susan could much more easily be self-sufficient, and Doug could do so much more good. With CR Rankings, in other words, citizens would have their most powerful and naturally fitting role by far.

As for the government, it too would finally find its most natural and effective role. Instead of futilely badgering the public to recycle more (citizen-focused approach) or crafting too few laws too slowly that businesses then do everything they can to avoid anyway (government-focused approach), the government would essentially here play the role of referee. It would collect the data, enforce that rankings be printed, and refine the system as needed. Being the referee might sound awfully unsexy, but it’s a crucial role that the government would knock out of the park. Think of tasks like collecting taxes, maintaining law and order, and running smaller programs like sanitation grades. The government has the massive size and unquestioned authority to smoothly referee these systems for hundreds of millions of people. It would similarly have the wide reach and power to collect the data needed for CR Rankings and mandate that the rankings be printed in a way that no NGO or private business could ever dream of doing. That’s essential to a system like CRR, and it plays perfectly to the government’s strengths. With CR Rankings, the government would ditch the awkward roles of the shaming parent and the slow, ineffective change-maker and finally get back to the role it does best: the referee.

Of course, sometimes we would still need the government to be that change-maker. Power plants are a great example. The government would still need to decide what kinds to build where. But in such situations the government would still be far more powerful and effective with CR Rankings around.

Remember how the number one priority of politicians is jobs? Currently that pushes them to do whatever will be cheapest for local businesses so as not to scare them away. That includes authorizing dirtier, cheaper power plants so as to keep the energy bill low for those local businesses. (It’s therefore no wonder the carbon-heavy coal and natural gas produce two-thirds of our electricity in the US.40) But with CR Rankings, businesses would get lower carbon footprint rankings when locating near such dirtier plants but would get higher rankings when locating near renewables like solar and wind. Businesses would thus have good reason to locate near greener power plants. Now to get all of those local jobs, politicians would for the first time be pushed in favor of, not against, building more such greener plants. The same would go for closing corporate tax loopholes, passing stricter labor and environment laws, etc. CRR would give the government much more power to work towards positive change. For the Political Polly and Pauls of the world, that means less yelling at CNN and more getting things done.

So all told, put those three roles together and you now have three groups each doing what it’s best suited to do, all in harmony together. Citizens would vote with their purchases to constantly push businesses to be more responsible. Businesses would then let loose their unique abilities to innovate and compete to produce the most responsible products and practices possible. All the while, the government would act as the referee, making sure everything runs smoothly, also now having the most possible power to authorize cleaner power plants and whatever other laws still needed to wipe out GCM problems. Together they would form a smooth, efficient machine for making the world a better place.

So to come back to the initial complaint, no, we would not be best served with a citizen or government-focused approach to change. Citizens, the government, and our businesses would all by far have the most power to effect change with the business-focused approach of CR Rankings.

So…Why Pick on Businesses?

So to sum up, businesses aren’t being unfairly picked on. They make most of the mess that causes GCM problems, so they need to be pushed to be more responsible or else we’ll never fix these problems. With CRR as law it would be mandatory for companies to participate, but all that that would require them to do is report the data and print the labels—a task that should be about as un-crippling as selling food in the US and having to print Nutrition Facts. CR Rankings would also not be cripplingly expensive for companies because the only changes companies would make would be those they choose to make (i.e., those changes they deem profitable). Plus, any extent to which companies would pay more to be more responsible just means cleaning the mess they’re already making, a mess they’re currently not paying to clean up. And finally, by thus focusing on businesses, we would simultaneously (and paradoxically) give much more power to citizens and the government to push for positive societal change, all while putting all three groups in their ideal roles to fix our biggest problems.

Businesses should absolutely be the focus in our quest to knock out GCM problems, and CR Rankings would do so in the most effective and business-friendly way possible.

Endnotes

1 Greenhouse Gas Inventory Data Explorer. Environmental Protection Agency, www3.epa.gov/climatechange/ghgemissions/inventoryexplorer/. Accessed 12 Dec. 2016.

2 “Table 1.2. Summary Statistics for the United States, 2005 - 2015.” SAS Output, US Energy Information Administration, www.eia.gov/electricity/annual/html/epa_01_02.html.

3 Fast Facts: U.S. Transportation Sector Greenhouse Gas Emissions 1990-2014. Environmental Protection Agency, nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPDF.cgi?Dockey=P100ONBL.pdf.

4 The 65% estimate comes from first adding together the greenhouse gases directly produced by the Agriculture (9%), Industry (21%), and Commercial (7%) sectors, which yields 37% of total GHG emissions.1 Then, the Industrial and Commercial sectors used 62.4% of nationwide electricity in 2014,2 yielding another 18.72% of GHG emissions (62.4% of 30%1). Finally, by combining the GHG emissions of Medium- and Heavy-Duty Trucks, Rail, Aircraft, and Ships, we get a rough estimate of 35% as the percentage of transportation GHG coming from businesses,3 which then gives us another 9.1% of total GHG emissions (35% of 26%1). Adding 37%, 18.72%, and 9.1% yields the estimate of 64.82% of total US GHG emissions at the hands of US businesses (which we then rounded up to 65%).

5 McKenna, Maryn. “Update: Farm Animals Get 80 Percent of Antibiotics Sold in U.S.” Wired, Conde Nast, 24 Dec. 2010, www.wired.com/2010/12/news-update-farm-animals-get-80-of-antibiotics-sold-in-us/.

6 Grube, Arthur, et al. Pesticides Industry Sales and Usage: 2006 and 2007 Market Estimates. Environmental Protection Agency, Feb. 2011, p. 12, www.panna.org/sites/default/files/EPA%20market_estimates2007.pdf.

7 In terms of the amount of pesticide active ingredient used nationwide, the agriculture sector tallied 80% in 2007 while industry/commercial/government tallied another 12%.6 We were not able to find information on how much of that 12% was used by the government, but we can overall then say that after taking out the government’s share of pesticide use, the agriculture, industry, and commercial sectors should account for 80-92% of 2007 pesticide use in the country.

8 Water Uses. AQUASTAT.

9 Employment by Major Industry Sector. US Bureau of Labor Statistics, 8 Dec. 2015, www.bls.gov/emp/ep_table_201.htm.

10 The 85% estimate comes from subtracting all government jobs from the total number of jobs in 20149 then finding the percentage those remaining jobs represent of the total (which yields 85.48%).

11 Vogelstein, Fred. And Then Steve Said, ‘Let There Be an IPhone.’ The New York Times, 4 Oct. 2013, www.nytimes.com/2013/10/06/magazine/and-then-steve-said-let-there-be-an-iphone.html.

12 Neate, Rupert. “Apple Calls 2015 'Most Successful Year Ever' after Making Reported $234bn.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 27 Oct. 2015, www.theguardian.com/technology/2015/oct/27/apple-2015-revenue-iphone-sales.

13 Shelanski. “Estimating the Benefits.”

14 U.S. Greenhouse Gas Inventory Report: 1990-2014. Environmental Protection Agency, www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/us-greenhouse-gas-inventory-report-1990-2014. Accessed 4 Sept. 2017.

15 Than. “Estimated Social Cost.”

16 64.82%4 of $247.3 billion = $160.3 billion

64.82% of $1.51 trillion = $978.8 billion

17 See endnotes 49-51 from Part III: Problems CRR Would Help Fix.

18 Jacobs. “The High Public Cost.”

19 Advancing Sustainable Materials Management: Facts and Figures. Environmental Protection Agency, www.epa.gov/smm/advancing-sustainable-materials-management-facts-and-figures. Accessed 20 Aug. 2017.

20 What Is U.S. Electricity Generation by Energy Source? US Energy Information Administration, 18 Apr. 2017, www.eia.gov/tools/faqs/faq.php?id=427&t=3.

21 Wilson, Alex. Saving Energy by Recycling. Green Building Advisor, 23 June 2010, www.greenbuildingadvisor.com/blogs/dept/energy-solutions/saving-energy-recycling.

22 “Learn about CFLs.” Energy Star, Environmental Protection Agency, www.energystar.gov/products/lighting_fans/light_bulbs/learn_about_cfls. Accessed 20 Aug. 2017.

23 How Much Electricity Is Used for Lighting in the United States? US Energy Information Administration, www.eia.gov/tools/faqs/faq.php?id=99&t=3. Accessed 20 Aug. 2017

24 Greenhouse Gas Inventory. Environmental Protection Agency.

25 “Table 1.2.” SAS Output.

26 “Heating & Cooling.” Energy.gov, Department of Energy, energy.gov/public-services/homes/heating-cooling. Accessed 20 Aug. 2017.

27 “Thermostats.” Energy.gov, Department of Energy, energy.gov/energysaver/thermostats.

28 Notes on how the 4.85% figure was calculated:

Doubling Recycling - Using 4.08 trillion kilowatt hours as the total electricity produced in the US in 201620 and an estimated 1.5 quadrillion BTUs of energy saved from recycling per year in the US,21 that means the energy savings from recycling is equivalent to 10.77% of all electricity generated in America (after converting BTUs to kilowatt hours and finding the appropriate percentage saved). Doubling recycling would thus give the same reduction in percentage of electricity, and since electricity creates about 30% of GHG annually,24 that means doubling all recycling would bring a 3.23% reduction of GHG production.

CFLs - Lighting uses 10% of all electricity in the residential sector,23 while 37.4% of all electricity used in 2015 was used in homes,25 meaning 10% of 37.4% gives 3.74% of total electricity used on home lighting. Given that 30% of all GHG produced in US comes from electricity use,24 30% of 3.74% yields 1.122% of those gases come from residential lighting. With estimated 70% savings in energy use from replacing all incandescent bulbs with CFLs,23 that means 70% of 1.122% gives a 0.79% GHG reduction from switching all lights in the country to CFLs (which is generous, given that many CFL bulbs are already in use, while this calculation assumes none already are).

Thermostat Adjustments – Residential use of electricity in 2015 was 37.4% of the total,25 and with 30% of GHG produced by electricity,24 that means 37.4% of 30% yields 11.22% of GHG produced by residential electricity. Add to that the 6% of all GHG produced directly by non-electricity home energy use,24 and we have 17.22% of total GHG coming from residential energy use. With 48% of home energy costs going to heating and cooling,26 that brings us to 8.27% of total GHG coming from heating and cooling homes. We then use the 10% estimated energy savings from the recommendations on adjusting thermostats from Energy.gov,27 multiply that by 8.27%, and we get 0.83% as the total GHG reductions from abiding by home thermostat recommendations on Energy.gov. Note that this calculation assumes no one is already abiding these thermostat recommendations, which is a generous assumption. The more people that already abide by these recommendations, the more this estimate should drop below 0.83%.

All told, 3.23% + 0.79% + 0.83% = 4.85% as the reduction in yearly GHG in the US if we were to double domestic recycling rates, replace all home lights with CFL bulbs, and get everyone to abide by thermostat recommendations for energy savings.

29 Population Growth (Annual %). The World Bank, data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.GROW. Accessed 20 Aug. 2017.

30 This calculation uses a ten-year average of US yearly population growth from 2007-2016 of 0.7968%29 (which is then rounded up to 0.8%).

31 To gain another 4.85% in population (and thus experience roughly the same growth in energy use) would take 5.94 years in a standard exponential growth model (when 1.0485 = e0.007968t, t then equals 5.94).

32 “National Recycling Rates, 1960 to 2005.” Waste & Recycling: Data, Maps, & Graphs, Zero Waste America, www.zerowasteamerica.org/statistics.htm. Accessed 20 Aug. 2017.

33 Advancing Sustainable Materials Management: Facts and Figures. Environmental Protection Agency, www.epa.gov/smm/advancing-sustainable-materials-management-facts-and-figures. Accessed 20 Aug. 2017

34 Bernasek, Anna. Volunteering in America Is On the Decline. Newsweek, 23 Sept. 2014, www.newsweek.com/2014/10/03/volunteering-america-decline-272675.html.

35 Charitable Giving Statistics. National Philanthropic Trust, www.nptrust.org/philanthropic-resources/charitable-giving-statistics/. Accessed 8 Oct. 2016.

36 Posey, Kirby G. “Household Income: 2015.” Sept. 2016, p. 2, www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2016/demo/acsbr15-02.pdf.

37 $2,974, the average household contribution to charity, is 5.7% of $55,775, the median US household income in 2015.36

38 Giving Statistics. Charity Navigator.

39 Sparshott. “Corporate Profits.”

40 What Is U.S. Electricity Generation. US Energy Information Administration.